The 1920s: Berlin, Paris, New York

Berlin, Paris, New York—such exciting places to be during the 1920s, an era variously known as “The Jazz Age” or “The Roaring Twenties,” but certainly never The Age of Innocence, which was merely the title of a book, albeit one of Edith Wharton’s most successful tomes.

Indeed, it was a stimulating, but far from innocent time, and the cultural climates of these cities seemed nearly ideal for books and their authors, composers and their music, architects and their buildings and creative minds in theater, film and art.

Recovering from Germany’s humiliating World War I defeat and an economy in ruins, the new Weimar culture embraced industrialization and surged forward to achieve an astounding level of intellectual production. Golden Twenties Berlin served as a magnet for writers and makers of art from many corners of the world: Christopher Isherwood stopped in briefly to join the nurturing atmosphere chronicled by Erich Maria Remarque (who wrote the timeless novel of war All’s Quiet on the Western Front) before writing his own Berlin Stories, immortalizing the period; the Brothers Mann, Heinrich and Thomas, and Vladimir Nabokov launched their remarkable literary careers there.

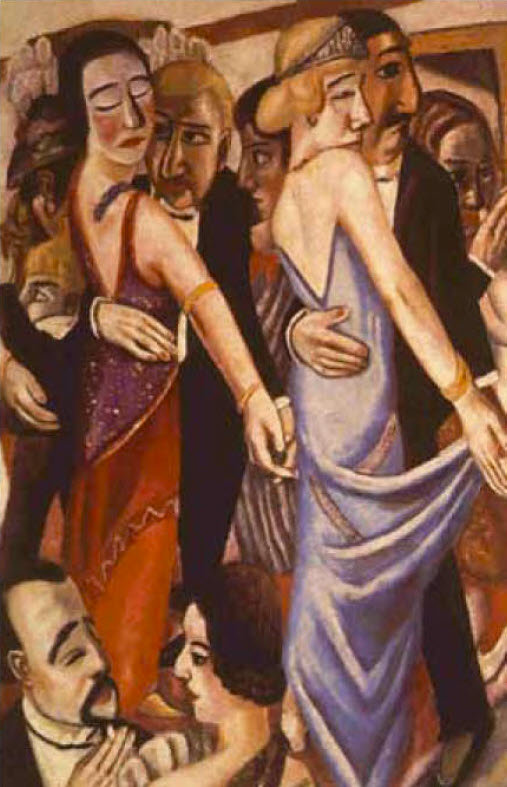

Dancing in Baden-Baden by German expressionist painter Max Beckmann, 1920

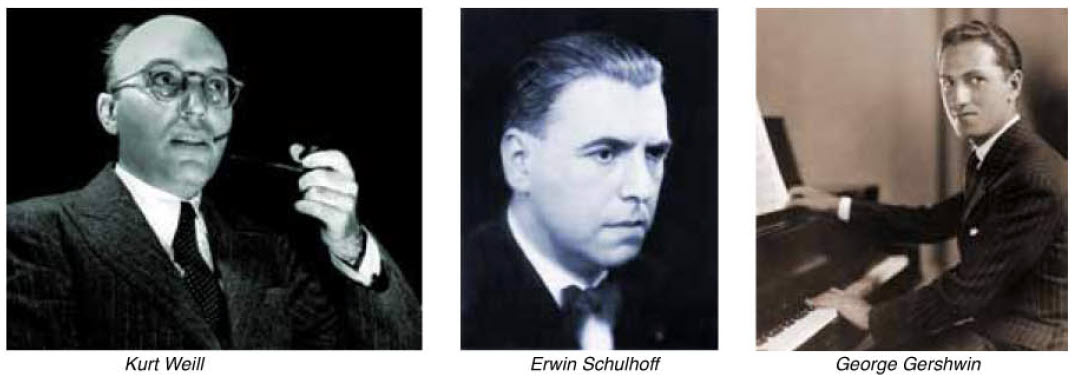

Erwin Piscator’s Das Proletarische Theater and other playhouses offered dramas by Bertolt Brecht and stage direction by Max Reinhardt. Concert halls performed the music of Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler (who provided scores for several Brecht plays), and Erwin Schulhoff who had emigrated from his native Prague.

Weill’s life took a few momentous turns in that decade: In 1922, he joined the “Novembergruppe,” a confraternity of leftist artists that included Eisler and Stefan Wolpe; he married the actress Lotte Lenya (for the first of two times!) in 1926, and two years later introduced his best-known work, The Three Penny Opera, a reworking of John Gay’s The Beggars Opera, in collaboration with Brecht.

Schulhoff, attracted to the influential Second Viennese School, also was drawn to the city by his friendship with Otto Dix, the Dadaist painter, and to others in the Berlin Dada movement, including George Grosz. Through Grosz, Schulhoff was introduced to American ragtime, dance music and jazz, which became a source of inspiration in many of his works from the 1920s.

Jazz enjoyed a warm spot in the hearts of Berliners, and African American entertainers, among them Josephine Baker, felt more welcome in Europe. Baker created a sensation with her “Banana Dance,” notably risqué for that time.

It may read like a catalogue, but all these personages create a splash of associations in an era overflowing with bold innovation and creativity. The Bauhaus, Walter Gropius’ radical concept to combine architecture, sculpture and painting into a single creative expression, sought a new system of living from students who were taught by some of the period’s most brilliant artists, among them, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Josef Albers. Similarly, filmmakers such as Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg (The Salvation Hunters, The Blue Angel) and Fritz Lang (Metropolis) made waves and still continue to find, and amaze viewers.

“Berlin, it is obvious, aroused powerful emotions in everyone,” observed Peter Gay in his intriguing volume about the era, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider. “It delighted most, terrified some, but left no one indifferent.”

Paris, in the opinion of Aaron Copland, was the center of the renewed post-war excitement in the arts. “Arriving on French soil, my expectations were dangerously high, but I was not disappointed,” he declared in his autobiography. Copland was there to study with Nadia Boulanger, the celebrated conductor, composer and teacher of many important 20th-century composers. George Gershwin, seeking instruction by Maurice Ravel, was told it was better to be a first-rate Gershwin than a second-rate Ravel, and was referred also to Boulanger. But after meeting with this remarkable woman and reportedly playing ten minutes of his music, he was informed that she, too, had nothing to teach him.

His response to the city resulted in one of his most popular compositions, “An American in Paris.”

Cole Porter alighted in Paris in 1917, before the great decade of creativity, and stories about him include his distribution of relief supplies and even service in the French Foreign Legion. Porter, who came from a well-to-do Indiana family, enjoyed the best of the City of Light’s social life and it was there he met, and married, Linda Lee Thomas, a rich, Louisville-born divorcée eight years his senior, who, few doubted, was aware of his same-sex proclivities.

Paris also was home to Les nouveaux jeunes, later known as Les six—George Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc and Germaine Tailleferre – friends who came in contact with Gershwin. They included Jean Cocteau in their circle, originally Erik Satie as a charter member, and enjoyed acquaintanceship with Serge Diaghilev, the impresario; Pablo Picasso, the painter; his colleagues Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró and Salvador Dali; René Clair and Luis Buñel, the filmmakers, and Maurice Chevalier, the popular entertainer.

They could all be found at one time or another in the salon of Gertrude Stein, also a haven for those literati who comprised the “Lost Generation,” a term generally attributed to Stein—Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Anais Nin, Henry Miller, and the list goes on. Many of these iconic characters come to life again, wistfully and humorously, in Woody Allen’s latest film, Midnight in Paris.

Gershwin, after a few months, returned to New York for the premiere of two projects on which he had been working—“An American in Paris,” performed by the New York Philharmonic led by Walter Damrosch, and his new show, Treasure Girl, with Gertrude Lawrence in the lead. The former enjoyed enduring success, the latter, not so much.

Porter, working on both sides of the Atlantic in 1928, enjoyed a major success with his new musical, Paris, commissioned at the suggestion of its star, Irène Bordoni. The show, which included two of those typically impish Porter songs, “Let’s Misbehave” and “Let’s Do It,” finally assured him a place in the select group of Broadway songwriters. “Le Revue,” staged at the nightclub Ambassadeurs, was hailed by Parisians and critics.

A year earlier, 1927, had been a landmark period for New York theater, with 268 plays on the boards, among the debutants, Jerome Kern’s and Oscar Hammerstein Show Boat with Helen Morgan, and the Gershwins’ Funny Face with Fred and Adele gliding across the stage. Others contributing to the musical cornucopia included the prolific team of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml, who both teamed with the ubiquitous Otto Harbach, and Irving Berlin, responsible for major contributions to the Ziegfeld Follies.

Ironically, the decade was welcomed, if one could use that verb, with the Volstead Act, but “hooch,” as it was known, still was enjoyed by most who wanted it, and the speakeasy not only invaded the vocabulary, but emerged as a central meeting place.

Also capturing attention were the abstract expressionism of Willem de Kooning, Surrealism and the American version of Dadaism of Georgia O’Keefe, and Realism expressed by Thomas Hart Benton, Edward Hopper and Grant Wood.

Dorothy Parker, Alexander Woollcott, Robert Benchley and George S. Kaufman met regularly with the other members of the fabled Algonquin Round Table, and W.E.B DuBois, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston were part of the Harlem Renaissance, the first important movement of black artists and writers in this country.

And then a rude awakening, the Great Depression, put an end to an American decade both boisterous in its joie de vivre and vibrant in its output.

In Europe, Nazism and the rise of Adolph Hitler were lurking just around the turn of the decade, and the freedom that offered so much creativity, as well as pleasure during the twenties vanished as the government branded virtually any non-traditionally German artistic achievement or anything by Jews, descendants of Jews or Africans “Entartete,” or degenerate. The exodus began.

Weill fled Germany for Paris and eventually settled in and around New York. Schulhoff, who returned to Prague, continued to compose, but his sympathies for communism became increasingly obvious in his music, and, when the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, he was imprisoned, and eventually dispatched to the Wülzburgconcentration camp in Bavaria, where he died of tuberculosis.

Eisler and Brecht, whose work was banned by the Nazis, fled first to Moscow, eventually finding refuge in the United States, where they collaborated until Brecht’s death. Eisler also found fortune in Hollywood, writing several film scores. But his political leanings made him suspect, and his name was among the first on the “Hollywood blacklist”; two investigations by the House Committee on Un-American Activities led to his being accused of being “the Karl Marx of music” and the chief Soviet agent in Hollywood—among the works he composed for the Communist Party was an anthem known as the “Comintern March.”

“I could well understand it when, in 1933, the Hitler bandits put a price on my head and drove me out,” Eisler declared in a departure statement. “They were the evil of the period; I was proud at being driven out. But I feel heart-broken over being driven out of this beautiful country in this ridiculous way.”

Gershwin met an untimely death, at age 37, in Hollywood amid continuing success—royalties to the Gershwin family continue to flow in, and in one estimate, during his lifetime, he was the wealthiest composer of all time.

Porter lived in pain during the final years of his 73-year life, due to injuries sustained from a horseback-riding accident. His life began in wealth, and his career, in later years, yielded significant successes, notably, the musicals Kiss Me, Kate and Can Can. He was one of America’s greatest lyricists, and the nimbleness of his words—mischievous, ironic, sometimes downright salacious, remain Cole Porter’s greatest legacy. In retrospect, we tend always to remember certain decades as ideal—many recall warmly the fifties as being a time of great prosperity, and for the rise of the middle class in this country. But it’s difficult to imagine any era as exciting, as stimulating, as creative, as the twenties—it did roar, it sang and danced, it emoted and brought forth images and shapes previously unimagined. Those were “the good old days,” and the world was young.