Shock Effect—Art and Scandal

Our closing concert of the season will examine shocking moments in music that, like an earthquake, changed the contour of the landscape for all future musical enterprise (Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, minimalism, John Cage, French aesthetic challenging German hegemony, the infusion of jazz and Latin vernacular into the classical stage, etc.) and often scandalized the public with their emergence. Several prominent artists and thinkers have expressed their observations about similar path-breaking moments and movements in literature, art, architecture, and theater, addressing the shock effect of “revolutionaries” who pushed open the door to modernism (Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon; mustache on the Mona Lisa, Dada; the 1914 Armory Show, etc.).

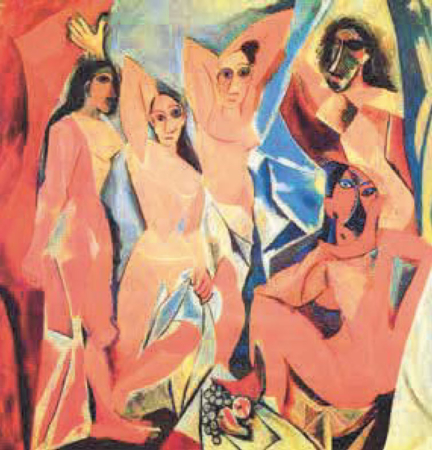

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,1907

How much was done for publicity’s sake, for the sheer joy of scandal and the impulse to rattle the bourgeoisie—and how much was the expression of an artist at a juncture…? We herewith offer a compendium of thoughts on pivotal early 20th century artistic events and personages.

Ed Smith, sculptor

Picasso: Things were different then, no phone, no television, no mass media. A different pace and movement before modernism….Demoiselles was the most ambitious painting ever by the most ambitious Artist ever…. It was by far the largest canvas he had ever tackled of women in a bordello, guaranteed to be shocking and unsettling, rivaling anyone with its primitivism and originality. The painting wasn’t exhibited but made an international stir, immediately prompting artists to travel from as far as Russia (a backwater) to Paris to beg Picasso to see the painting. What a thought! A painting was not a window but a thing unto itself…. A painting could be “about” what was seen AND what was known but unseen. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was a rough new brutal reflection of the contemporary modern world fusing time and space.

Rodin: Such hopes and expectations rode on this monument of Balzac. Years of work, study and investments of time and personal money. Just the mere physical labor of working on this figure would crush any lesser artist. To represent the Republic’s genius embodied in its greatest writer was a Herculean labor.To push and lift the public to recognize the genius of Honoré de Balzac was beyond possibility. Rodin briefly flirted with the idea of portraying him nude. Ultimately, though, his intention was less about creating a physical likeness of Honoré de Balzac than communicating an idea or spirit of the man and a sense of his creative vitality. It was a defeat for Rodin… but lit the way for sculptors for decades. The Balzac represents a new vision of the Artist by the Artist in society. While France could accept the Thinker, Balzac was de trop—too much, too far into the future… too brilliant for its time.

Auguste Rodin’s Balzac, commissioned in 1891 and finally cast in 1939

To quote Rodin: “I think of his intense labor, of the difficulty of his life, of his incessant battles, and of his great courage. I would express all that.”

Ubu Roi – Alfred Jarry: Imagine tumult, opening night…. Shoving, pushing, anticipation, the noise, the frisson of expectation…. The lights dim and an actor clumsily moves to center stage. While The King of Poland (a joke even then), Pere Ubu, looks out onto the audience, they quiet down…. They are experiencing the world anew in daily life in Paris, seeing changes in society, industry and art. A hush descends on the theater as the actor reads the words of the modern playwright, the diminutive genius Alfred Jarry. They wait… his mouth opens… the audience gasps… “MERDE!”

And the modern world of pandemonium erupts.

Alberto Manguel, author

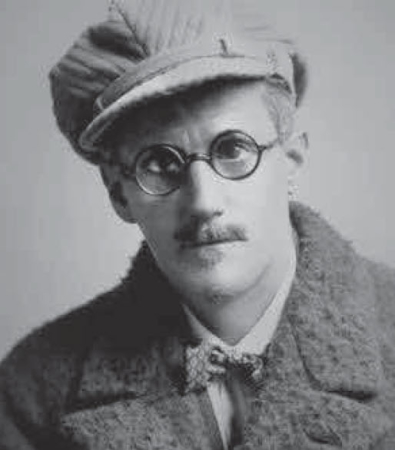

The Shock of the New: Originality as a positive value is a fairly new concept in art. Up to the 19th century, the impact of a work of art was not measured by how radically it broke with the ideas of the works that preceded it but by how strongly it voiced ongoing questions. Oscar Wilde perceived the difficulty precisely: “The originality which we ask from the artist is the originality of treatment, not of subject. It is only the unimaginative who ever invent.” Building on Wilde’s argument, artists began to treat the traditional by radically changing its presentation. In two decades, from the late 1890s to the early 1920s, three U’s changed forever the vocabulary of art. In 1896 Alfred Jarry rendered the classic epic drama in the tradition of Macbeth as a brutal and vulgar buffoonery with Ubu Roi. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp presented his ready-made urinal with the title of “The Fountain” and proved that art is anything exhibited in a museum, as long as the artist sees it as such. In 1922, James Joyce published Ulysses reclaiming for the genre of the novel all possible forms and styles to tell the ancient Homeric story. These works all provoked scandal not by saying anything new but by saying it in new ways, or rather in ways that the audience didn’t comfortably expect. After Jarry, Duchamp and Joyce the role of the artist is to unsettle.

Michael Chertock, pianist and conductor

I tend to divide Shock Art into two categories: Gestures designed to shock and scandalize the audience for no other purpose but to disturb and bring attention to the artist (Shock Art)…. And amazingly conceived and brilliantly organized works, so creative and original that for years afterwards fellow musicians and artists wonder, Why didn’t I think of that? For instance: a play set during the Salem Witch Trials that serves as an allegory for the Communist witch hunt… Memento, a non-linear film in which the plot runs backwards and forwards at the same time, one narrative in color and one in black and white… Westside Story, a retelling of Romeo and Juliet set in the tough streets of New York… When Doves Cry, a mega pop hit with absolutely no base line (Art developed from an audacious idea).

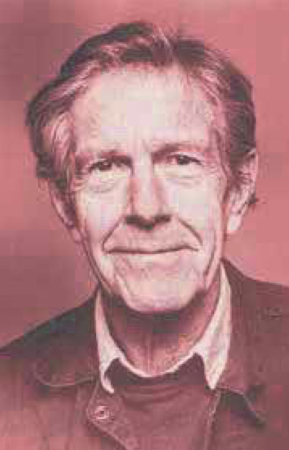

I was recently amused by the reaction of my 17-year-old daughter when I described to her John Cage’s 4’33”, a piece for piano with no notes, music or sound, simply elapsed silence. Her eyes went wide and she asked “Is that even music?” I think John Cage would be pleased.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring taps into something volcanic in its primitive power. It is hypnotic and unsettling. The listener feels at times like they have stumbled into a convulsive dimension of fear and fascination….It is impossible to turn away as it crawls, leaps and staggers to its conclusion.

Jorge Martin, composer

One could argue the decisive demolition of the European art music tradition came when John Cage pronounced that noise, too, was music. His notorious 4’33” of silence (1947-8) may be seen as the silence offered as requiem to that tradition. In a series of scandalous gambits of one-upmanship that Dada instigated, this was the crowning Nya-Nya. If music is just an attitude we bring to hearing, as putting a frame around anything in our field of vision makes it art, then everything is art—oh, wonders!—but not by the ancient understanding of art as the making or bringing into being of a numinous object expressive of the human condition. So we live in a post-art age. People still paint and sculpt and write music and novels and poems but Art is dead as God is dead: neither ever really dies but lives on in medicated, technology-addled sedation. After Cage’s coup the only possible, honest response was minimalism, attempting to strip Western music of its pretensions under the guise of “mindlessness,” an Eastern meditative import, but itself a pretense, as the music’s motoric repetitiveness expresses the essence of the soulless machine, not the organic rhythms of the human breath. Dada was the naughty flower of the Romantic myth of originality; now it has withered, shock is passé. Perhaps the only really shocking thing now would be the terrifying reawakening of God, and Art.

Paul Schoenfield, composer

Regarding shock in the arts, I can think of no improvement upon the words of the philosopher, Roger Scruton:

“A century ago Marcel Duchamp signed a urinal with the name ‘R. Mutt’, entitled it ‘La Fontaine’, and exhibited it as a work of art. One immediate result of Duchamp’s joke was to precipitate an intellectual industry devoted to answering the question ‘What is art?’ The literature of this industry is as tedious as the never-ending imitations of Duchamp’s gesture.”