Intoxicating Dreams: German Orientalism

By Amala M. Levine

Keenly aware that Germany had no colonial presence in Asia, Heinrich Heine observed in 1821 that, while Portuguese, English and Dutch commercial ships might transport the material riches of India to the West, Germany would not fail to mine its spiritual treasures. He called August W. Schlegel, Franz Bopp and Othmar Frank “our own contemporary travelers to East India.” Anchored at German universities, these founding fathers of oriental linguistics and literature were cultural voyagers who intellectually unlocked the mysteries of the East through the academic study of ancient Sanskrit texts. At the time when Heine discovered his enthusiasm for the beauty of Indian poetry, the German fascination with the mysterious East had reached a peak and a turning point.

Heinrich Heine

Awareness of a world east of classical Greco-Roman antiquity spread slowly in Europe. The ancient Silk Road had established a first link between East and West in the 1st century BCE, bringing cultural exchanges along with silks and spices. Much later, the voyages of Marco Polo, followed in the 16th century by Portuguese galleons and Jesuit missionaries, carried information of magic lands, great empires and Confucianism to western shores. Some of this information seeped into Germany, where Leibniz in 1679 published a collection of Chinese documents entitled Novissima Sinica, proclaiming that “everything exquisite comes from the East Indies.” Leibniz was the first to speculate that the “ancient technology of the Chinese [Confucianism] can be harnessed to the truths of the Christian religion.”

Gradually through the 18th century, the fascination with all things Asian started to build. Herder, the first German cultural anthropologist, in 1784 turned to the “Orient, soil of God,” as the source of human origins. For him India represented an age of innocence, the childhood of humanity, of religiosity, and closeness to nature. By that time, he already had pioneered comparative philology with his Treatise on the Origin of Language [1771] and translated into German from the English some verses of the Bhagavad Gita. Herder’s iconoclastic interests and intellectual acuity shaped the sensibility and interests of the young Goethe as well as the Romantic poets and philosophers, from Novalis to the brothers Schlegel, to Schelling and Schopenhauer.

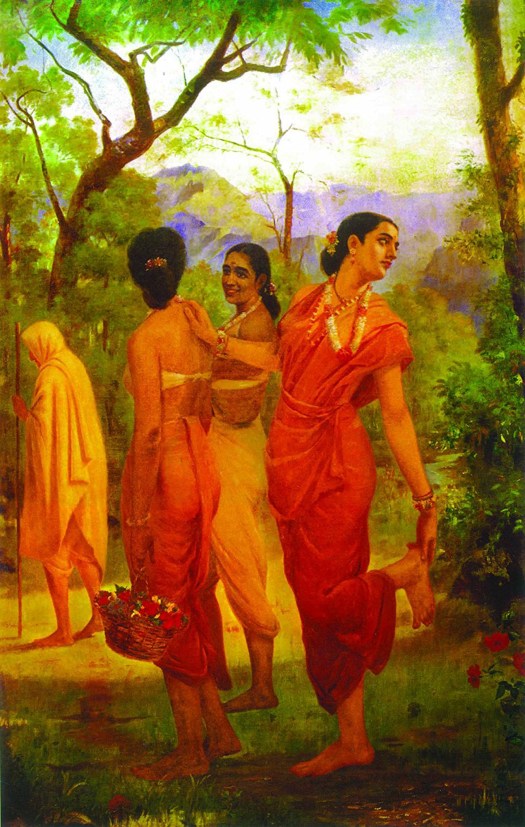

“Shakuntala – Looks of Love” by Raja Ravi Varma

Herder also revised the second edition of Sakontala, first translated into German by Georg Forster in 1791, unleashing a veritable Sakontola frenzy in Germany. The Sanskrit play Shakuntala, created by Kalidasa between the 1st and 4th century CE and based on a love story in the Mahabharata, was a sensation. Herder called it “my Indian flower,” Goethe composed a poem declaring, “All that is needed is done/ when I Sakontola name,” and Novalis, in moments of emotional intensity, addressed his fiancée Sophie as Sakontola. In 1820 Schubert composed, but only half-finished, the opera Sakontola. India had thoroughly captured the German imagination.

From 1798 to 1800, Friedrich and August Schlegel published the Athenaeum, the mouthpiece of German Romanticism. There Friedrich Schlegel formulated his aesthetic theory of Romantic poetry as “a progressive universal poetry” and pleaded for “a new mythology [that] can emerge only from the depths of the spirit.” He reasoned it could be found, “if only the treasures of the Orient were as accessible to us as those of antiquity. What new source of poetry could then flow from India…In the Orient, we must look for the most sublime form of the Romantic.” To gain first hand access to the ancient texts of India, he studied Sanskrit. It turned into a revelation.

In the Vedas and the lyric poetry of the great Indian epics, Schlegel found the spirituality, beauty, mysticism, and unity with nature that corresponded to German Romantic pantheism, metaphysical yearning and the search for universality. Though Schlegel had a tendency to excessively idealize and later, after converting to Catholicism, turned a rather dour, conservative eye on his early oriental enthusiasms, he did lay the groundwork for the fascination with India and the Orient that flourished throughout the 19th century.

In 1803, Schlegel wrote to the German poet Ludwig Tieck, that he believed Sanskrit to be the Ursprache, “the source of all languages, all ideas and the songs of the human spirit; all, all stemmed from India. I have gained a completely different view and insight on many things since I can draw from that source.” When he published On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians in 1808, grammatically linking Sanskrit and Indo-European languages, he offered an alternative to the rationalist aesthetic of ancient Greece and, not coincidentally, to the French Enlightenment. His vision of India had everything they had not.

One should not underestimate the shock and excitement of Schlegel, his fellow Sanskrit scholars and poet friends at the discovery of an entire ancient system of religious thought, mythology and poetry that was still breathing with life, against which Greco-Roman classicism seemed the pale shadow of a dead past that championed reason rather than the imagination. Schlegel exuberantly spoke of an “Oriental Renaissance,” hoping it would have the same transformative effect on Europe as the humanistic Renaissance 300 years earlier.

The yearning for a universal religion and transcendental progressive poetry found nourishment in the idealized conception of the Orient the Romantic poets derived from the newly translated Sanskrit texts like the Gita Govinda, the Ramayana and the Baghavad Gita. Even Goethe, generally more classicist than Romantic, jumped onto the band wagon by including orientalizing poems in his last great poetry cycle, West-Eastern Divan (1814-19), which Heine celebrated as a superb example of “our [new] lyrics [that] are aimed at singing the Orient.” Novalis likewise proclaimed that “It was in the Orient that the true treasures of romantic poetry lay,” and Hölderlin dreamed of a “Dionysian” Asia as the source of regeneration. Spiritual and literary interests merged, as did those of philosophy and religion. Schelling, in his Philosophy of Mythology had already in 1799 proposed a common mythology shared by all peoples and a “single God for all mankind.”

Schlegel’s glorification of ancient Asian civilizations coincided with a time of turmoil in Europe. The Napoleonic wars raged from 1799 to 1815, involving the entire continent, including England. The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, a nominal rather than actual power, finally collapsed in 1806, leaving more than 300 German principalities feuding in political disarray. It was time for Germany to forge a common national identity.

Again Friedrich Schlegel, building on Herder’s hypothesis of oriental origins, was trail blazing by suggesting that Germans, speaking an Indo-European language, were indeed Aryan migrants from northern India via Persia. His intoxicating dreams of a German-Aryan connection did not have the racist dimension they would acquire by the mid-19th century. His sole intention was to create a northern European cultural counterbalance to the predominance of the French and classical antiquity.

By 1830, Oriental Studies were flourishing at German universities, now the preeminent domain of Indology, Sinology and Comparative Linguistics. By the mid 40s, Max Müller, a student of both the philosopher Schelling and the linguist Bopp, had translated the Upanishads into German and subsequently published 50 volumes of Sacred Books of the East in English. Unintentionally, he was among those who contributed to the racialist undertones that increasingly crept into academic Oriental Studies. Like the Romantics, Müller linked linguistics, culture and religion, pointing out common Indo-European/Aryan traditions. These theories were gradually distorted by anti-Semites like Arthur de Gobineau to suggest an Aryan racial superiority. From the1850s, the intoxicating dreams of early German Orientalism acquired distinctly racial shadings, devolving ultimately into the delusional nightmares of Nazi racist propaganda.

Outside the walls of academia, Orientalism grew apace in popularity. The new passion for oriental décor, vivid patterns and colorful oriental costume now competed with the modest restraint of Biedermeier and classicist furnishings. Mme de Stael traveled through Europe, draped in bright silks and elaborate turbans, for years accompanied by A. W. Schlegel who, with his brother Friedrich, had helped spread the orientalist gospel. This fascination with the exotic East, with pagodas, pugs and porcelain only increased as the century progressed. Odette’s chrysanthemums and lacquered screens in Proust’s fin de siècle masterpiece sprang from the same Asian ground as Heine’s “Lotus Flower,” so beautifully set to music by Schumann.

By the early 20th century, when Mahler composed Das Lied von der Erde, he used Hans Bethge’s German translation of Chinese poems, Die Chinesische Flöte, to express his own melancholy mood at the transience of life. The third and forth movements musically and lyrically evoke the Orient, as girls gather lotus flowers and young men meet at a porcelain pavilion. Though Mahler’s composition is far from a slavish adaptation, it shows how deeply the East had penetrated the Western mind. Hermann Hesse’s work exhibits a similar fusion.

In 1916, Hermann Hesse, one of the few Germans to actually travel to India before WWI, called the spirit of the East “a comforter and a prophet. For never can we, the elderly sons of the West, return to primeval humanity and the paradisial innocence; but surely homecoming and fruitful renewal beckon to us from that ‘spirit of the East’.” Hesse wrote Siddhartha in 1922 and Journey to the East in 1930; both slender volumes have retained their popular appeal until today, especially among the young.

While Hesse hoped for spiritual renewal, the exiled former Emperor Wilhelm II took a more racially inflected stance in 1928, when he mused in a conversation with Oswald Spengler that Germans “are orientals and not westerners.” Finally, in the 1930s, Germany descended into the Aryan nightmare of the Third Reich.

Today the Far East is only a plane ride away. Ashram tourism, yoga, meditation, and Buddhist conversions have become an accepted part of a multi-cultural Germany. Once again, dreams of the East are benignly intoxicating.

Dr. Amala Levine is an academic lecturer and founder/president of The Millbrook Symposium, offering biannual symposia in the world of ideas and literature.